Reprinted with permission of Altadena Heritage.

The article first appeared in the Fall/Winter 2016 issue of the Altadena Heritage Newsletter

The theme of our fall/winter newsletter has been controversial for 100 years: the effects of Hollywood and filming in Altadena. Some digging provides historical perspective on the industry that helped expand California’s economy into the largest in the U.S. and sixth largest in the world, even as it can strain neighbor relations and baffle many who simply want to know what the rules governing location shoots are, and if and when they are enforced.

A New Regional Industry

|

| This Altadena Victorian cottage was turned into a winter wonderland for a U.S. Postal Service shoot. Photo by Russ Fega. |

Altadena’s documented claims on early Hollywood glamour, however, seem to have had more to do with millionaires, social connections, and alcohol than as a filming location. Films were shot here — but since most were not directed by lionized filmmakers such as Griffith (who went on to direct Birth of a Nation, which was first acclaimed, and later condemned for its racism and glorification of the Klu Klux Klan), not much paper trail exists.

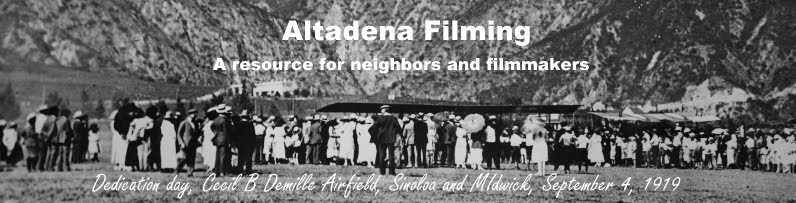

Our community was viewed as a “district” of Pasadena best known for wealth, mansions, hotels, and tourism. In 1919, Paramount Pictures’ Cecile B. De Mille opened an airfield — his third — on leased land adjacent to the Country Club (established in 1911, often called the Pasadena Golf Club) on Mariposa Street — in partnership with Pasadena’s Board of Trade and the Linnard Hotel chain. The movie mogul grasped the synergy between the sexy new civil aviation industry and his own, and established the Mercury Aviation Company to profit from it. This company offered the country’s first scheduled flights, and built DeMille Fields #1 and #2 in Hollywood and Beverly Hills. Stunt flying was heavily featured in early films, and our local airfield and Country Club hosted aviators, actors, and assorted hangers-on.

|

| Actress Gloria Swanson in Don’t Change Your Husband, (1919) |

Prohibition, Filmites, and Real Estate

People poured into booming Prohibition-era Southern California, and Altadena was among its fastest-growing communities. Airfield #3 lasted only until 1921, when the value of its 30 acres soared. Pasadena’s Board of Trade lost its lease, and tony new homes on some of Altadena’s last open land proliferated around the Country Club.

As a private club in unincorporated Los Angeles County, this facility escaped Pasadena’s primness and strict alcohol-law enforcement. Perhaps that prompted Italian immigrant Joseph Marcell Annechini in 1923 to re-imagine his downtown Los Angeles watering hole as a remote Altadena “Country Inn” with gardens and private rooms at top of Lincoln Avenue. There, land was affordable and the heat was off. His film industry clientele happily followed the searchlight beacon mounted atop the Marcell Inn to Annechini’s new speakeasy, and Hollywood gossip columns through the 1930s are peppered with references to it as a place actors such as Buster Crabbe and Frances Ford, famed studio executives, and racetrack gamblers entertained — even after some were caught in a 1924 federal raid that yielded 300 arrests.

As a private club in unincorporated Los Angeles County, this facility escaped Pasadena’s primness and strict alcohol-law enforcement. Perhaps that prompted Italian immigrant Joseph Marcell Annechini in 1923 to re-imagine his downtown Los Angeles watering hole as a remote Altadena “Country Inn” with gardens and private rooms at top of Lincoln Avenue. There, land was affordable and the heat was off. His film industry clientele happily followed the searchlight beacon mounted atop the Marcell Inn to Annechini’s new speakeasy, and Hollywood gossip columns through the 1930s are peppered with references to it as a place actors such as Buster Crabbe and Frances Ford, famed studio executives, and racetrack gamblers entertained — even after some were caught in a 1924 federal raid that yielded 300 arrests.Industry types were gravitating to Altadena, and one, David Haney, planned in 1923 to develop a “film colony” and studio here for his production company, “The Popular Players.” The plan was defeated by the Altadena Citizens’ Association, whose spokesman W.S. Grassle said: “We do not want motion-picture people in the neighborhood . . . We have had enough of that sort of thing from the Hollywood Companies . . . They bring noise, confusion, and an undesirable class of people with them. We have no liking for film actors in Altadena.”

It was too late. For better and for worse, Hollywood had discovered Altadena. The Los Angeles Times of the 1920s and 30s is full of reports of “filmites” such as May Marsh, “looking blooming as a rose. . . coming into town from her Altadena home” long enough to sign a contract to star in a series of films. Screen actress Barbara La Marr, known as the “too beautiful girl,” died at her Boston Street home in 1926 — and lay in state for several days to accommodate grieving fans.

Tinseltown scandal also scampered up our slopes: the 1922 shooting death of director William Desmond Taylor was linked (perhaps erroneously) to his plan to testify against girlfriend Mabel Normand’s cocaine dealer. Normand, the last person known to see Taylor alive, disappeared after his murder to “her bungalow at 1101 Foothill Boulevard” (now Altadena Drive). While never charged, she was nonetheless tarnished by the incident; her parents rushed from New York to nurse “the winsome comedienne’s” nerves that had barely recovered when, in 1924, millionaire oil broker Courtland Dines was shot with Normand’s pistol. Apparently, the driver did it.

Hollywood’s early boisterousness calmed toward the end of the Depression and through World War II — at least in terms of newsworthy references to Altadena. Undoubtedly, filming in Altadena continued to grow as the industry expanded.

But until 1982, only cities — not Los Angeles County — considered regulating filming or keeping data on it! At the end of that year, the Board of Supervisors finally proposed “Strict Curbs on TV, Movie Filming in Unincorporated Areas,” according to the Los Angeles Times. An Altadena home “used for filming five times in six months” was cited by the county planner responsible for the zoning ordinance requiring production companies to obtain permits from a new “filming coordination office.” Limiting shooting days to 10 a year per property (with extensions possible), and requiring that production companies pay the costs of sheriff and fire department services were parts of the ordinance passed January, 1983.

Modern Times

Since then, Los Angeles County has revoked and revised, rethought and redelegated enforcement of filming policies in its unincorporated areas many times.

Because problems and confusion about permitting persists, the Altadena Town Council recently established a subcommittee led by Ann Chomyn to gather and disseminate information about filming. Most Altadenans appear to value filming’s contributions to our local and regional economy, yet want reasonable limitations that enforce rules and stop the overuse of a small number of properties.

|

| Jeff Bridges photographed on the porch of Altadena’s Woodbury House during 2010 remake of True Grit. |

In 2014, the Milken Institute reported that California had lost 16,000 production jobs over the previous eight years — most to New York, which grants film tax credits four times higher than those allowed here. Other states and Canada also offer greater incentives.

Filming in Altadena Today

Sharon Northrup, who handles filming for Mountain View Cemetery and Mausoleum (established in 1881, it is Altadena’s oldest continuously operating business) says community filming relations “all come down to communication, very careful scheduling, and good production companies. The people we work with are great.” Crews film about 10 days a month there (more than anywhere else in Altadena). This supplements Mountain View’s regular income and helps maintain its 62 acres, while allowing for capital projects such as resurfacing roads. The Mausoleum lot is also used as “Base Camp” for other productions in Altadena, so that actors and employees can park there and be shuttled to shooting locations.

“Because we have room for parking, we don’t disturb neighbors much,” she says. “We also schedule filming to not interfere with services or funerals. If conflicts arise — say, people we hadn’t planned on turn up to visit — the production company knows it has to stop until we say go.”

Mountain View’s traditional business remains its core, but Northrup says filming is crucial to its financial health. “But you never know when filming might go away. It was down (after the 2008 recession) but seems to be coming back.” She added “Local restaurants get lots of business; we work with the same companies, and their crews all know about Fair Oaks Burger, Pizza of Venice, El Patron, and others. . . Fair Oaks Burger even got a little shoot of its own.”

Filming at Zorthian Ranch, another Altadena institution, has helped Alan Zorthian keep his head above water in maintaining that 45-acre piece of open space.

“We’ve done quite a few music videos: Sean Lennon, One Direction, etc., fashion shoots, and one TV Show, Aquarius, with David Duchovny playing a detective in the 1960s dealing with a Manson-esque sort of cult,” he says. “Most of the people we work with are responsible, and they really like shooting up here. They know they have to behave or they might not get to come back,” he said.

|

| 2010 episode of CSI:

Miami Photo by Tom Davis |

The Future of Filming

But it would be better for regional prosperity and good neighbor relations if the rules were more understandable. The County has to respond to changing circumstances, but reinventing the wheel every 10 years without much transparency has forced some residents to press for clarity. Particularly in “problem” locations and blocks, designating a number of shoot days allowed each property, as in the past, and possibly cap total days permitted on the block, would benefit everyone. In the long run (we hope Hollywood continues its long run, and includes us!) clear, fair rules equitably enforced are the best way to spread the magic, and the wealth, of Hollywood to Altadena.

Could you help me? I'm looking desperately for this cottage in your article! It is a filming location that I'm looking for for years now!

ReplyDeleteHi Gianni. Sorry to say that I do not know where the cottage is.

ReplyDeleteHowever, you might be able to find the location by contacting Russ Fega. He took the photo -- in fact it appears here with his permission. You could try contacting him through the HomeShootHome web page. Here's the link: http://homeshoothome.net/

Hope that helps.

Hi Kenny Meyer!

DeleteI already found it on Russ Fega's website! But thank you very much for your quick answer.

Gianni3004, What else is the Victorian from? I'm really into filming locations but it doesn't look familiar to me, so I'm just curious. :)

DeleteHI Gianni3004. Sorry I can't help there, but I see that you found Russ Fega's website. He will know. Perhaps he's willing to help. I recommend reaching out to him.

DeleteIncidentally, you can see a history of filming at many Altadena adress by going to the filming map. https://www.altadenafilming.org/p/altadena-filming-frequency-map.html. If you click on one of the orange markers, a legend will pop up. That legend includes a link to table that shows what was filmed at that location between '08-'18. Hope that's useful.